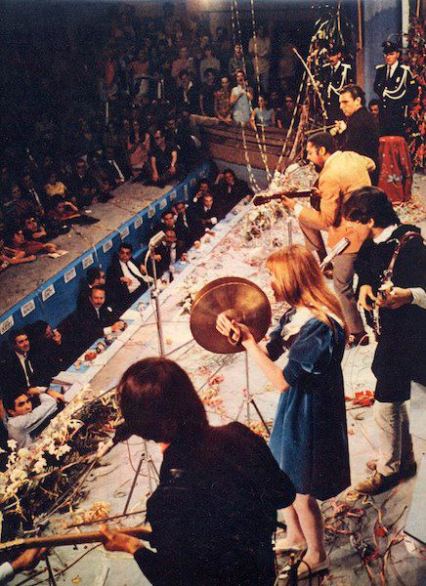

Célia was the pretty and skinny girl from the eleventh floor when we lived in Copacabana. She was friends with Sarah and one day she rushed in very excitedly to say that her Mum had given her two tickets for the International Song Festival for her birthday and, to my desperate envy, she invited my sister to come. The mega-event was in the Maracanãzinho, the Maracanã’s smaller brother, set up right next to it to host non-football related events. This was a unique opportunity to watch the best artists in the country and other big international attractions live. This was something that went beyond what Eurovision is nowadays, the regime hoped to unite the nation around them and the artists that the organizers chose with the backing of record labels represented all segments of Brazilian society. The intellectual left would have Chico Buarque, the bossa nova purists would have Tom Jobim and Nara Leão, the rockers and psychedelics would have Os Mutantes; the black people would have Toni Tornado, the militant university students would have Geraldo Vandre, the tropicalistas would have Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso; the samba lovers would have Jair Rodrigues and Paulinho da Viola; and then there was Jorge Ben who pleased everyone.

These contests grabbed Brazil’s attention and the relatively recent TV stations transmitted them to the millions of televisions recently bought to watch the World Cup in Mexico. The military felt proud to demonstrate that, although they did not allow their people to choose their administration, they had nothing against freedom of expression. This was only half-true, with the press closely watched and limited in its freedom, the festivals assumed the status of perhaps the only forum where the debate about the country’s reality could flourish. Although there was also an undeniable commercial aspect them; they represented a break with the Bossa Nova and with the old generations of radio stars and starlets. Most of the successful artists would end up filling the coffers of the record labels and father everything that came after them.

Many songs were indeed political, while others were about the catching up with the hippy revolution that was going on outside the country, and competed side by side with pretty love songs and happy sambas. However, the political controversy of the two main trends would end up in the inevitable clash between the hard-core Bolschevic revolutionaries and the flower power crowd, which caused strange events such as a rally against the electric guitar with the presence of eminent journalists and Gilberto Gil.

The effervescence of the repressed youth, tired of the solutions presented by the traditional left and by the traditional right, would make the festivals the stage of a cultural debate, perhaps too important to the liking of their sponsors. Parallel to this there were other important cultural expressions appearing in the art world, in cinema, in the theatre and in literature. On the other hand, there was a lot happening in terms of political and cultural uprising outside Brazil. Altogether, the nation hungered for expressions that mirrored their life experiences and expectations in times of deep changes. The tropicália movement would emerge from this moment. Although it is currently associated with Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and Os Mutantes the movement was much wider in its proposal and almost amorphous in its positioning. Under its big umbrella, there was nationalism, folklore, pop, sympathy for the Cuban revolution, love for the Beatles, Samba, and search for the roots of Brazil. Before going commercial and dissipating, the tropicália encompassed graphic artists, such as Hélio Oiticica, avant-garde musicians such as Tom Zé, journalists, writers, philosophers, intellectuals and a plethora of crazies and geniuses that still influence the current days.

What kept all those tendencies together was the opposition to the regime and to Brazil’s enormous social disparities that its rulers were unwilling to deal with. As the political grip tightened, the military realized that echoes of a creative explosion landing inside the nation’s living rooms was complicated. Many of these festivals winning artists, and definitely the most popular ones, exhibited too much creativity for the ideologues of the coup and, worse, many openly voiced their opposition to the state of things. For the military, stopping the party or excluding the stars would send out the wrong message, the way out was censorship.

After the AI-5 decrees, that took away all basic civil liberties from Brazilians, things turned to the worse. With no judicial system to answer to, the country’s rulers resorted to exiling and jailing artists, and the festivals died out.

A few years later, the military allowed the artists back as a gesture of reconciliation. More than their music, their fans missed the political and the libertarian overtones in their songs. They returned as heroes but had matured abroad and now they had even more professional agendas. Their concerts acquired a special quality, mixing an authentic resistance pedigree, celebrity status and world-class musicianship. When Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso and Chico Buarque played, the world seemed to come back to normal.

This was the time when I began going to shows. They were huge events, closer to football matches and political rallies than to musical concerts. When the doors opened the audience rushed in like cattle, and when everyone had taken their places, there was a similar atmosphere to being in the Maracanã. It was a lot of fun; the several sections of the theater booed and cheered each other as if they were supporting different teams. They also sang choruses with related and unrelated themes some of them political, some of them related to drugs and some of them just plain funny.

When the lights went down, the room fell silent and the magic began. In the best concerts, one felt as being in the artists’ lounge. The calmer songs provided a communal atmosphere that I have never experienced anywhere else and the more rhythmic ones, always saved for the end, resulted in out of season carnivals with the entire theater dancing on the chairs, in the corridors and on the stage.

Parallel to these concert-parties with political innuendos, there was something new creeping in. Rock bands were the expression of the new generation and were the underground of the underground. Their public was frightening: they looked dirty, had much longer hair than the average and took drugs that most people did not even know existed. One of the main expressions was Raul Seixas, his lyricist, Paulo Coelho touched on mystical and sex related subjects close to what bands such as Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones were doing in the international Rock scene. There was also the Secos e Molhados who adopted and androgynous style and make up that the American band Kiss would copy, and that surpassed many international bands in terms gay openness as early as 1972. These artists, although popular with the youth, shocked everyone and in intellectual terms, no one liked them, not even the Lefties.

As far as behaviour is concerned, they pioneered everything that most people would consider banal in the following decades, drugs, vegetarianism, and interest in mysticism and in oriental philosophies and the following of a sort of zen-individualist outlook of life. As Ipanema’s surfers, the rockers did not have any agenda other than living their lives intensely and ignored both the political dictatorship of the right and the intellectual dictatorship of the left. When disco kicked in, they discovered that looking good and shaking their moneymaker on the dance floor brought in more sex. This, and the large amount of drug casualties made that generation of pioneers mutate and vanish quickly.

With the gradual interchange of these two generations, the concerts slowly ceased to be about resistance to become simply a breath of fresh air from the claustrophobia of both the regime and of the audience’s homes. It also became more and more obvious that this was a rich kids’ club: in order to forget the military for a couple of hours, hang out with the cool crowd, buy the right records, go to concerts, and travel to alternative destinations, you had to have money and it was not everyone who had access to those luxuries.

There were never any representatives of the working class in the room. The masses weren’t hip: they were still the maids who had prepared our dinner, the bus drivers who had taken us there, the guys in the street who asked to look after our cars or and the policemen outside hungry to extort our money. The rebels from the less privileged classes listened to funk and went to their own parties, as portrayed in the film “City of God”, a true story of this period of Rio’s history.

back to first chapter next chapter

Filed under: Book Tagged: book on Brazil, books on Brazil, Brazil, brazilian culture, brazilian history, Brazilian music, brazilian rock, Caetano Veloso, Chico Buarque, Geraldo Vandré, Gilberto Gil, information on Brazil, information on rio de janeiro, Jair Rodrigues, Os Mutantes, Paulinho da Viola, Paulo Coelho, Raul Seixas, Rio de Janeiro, Roberto Carlos, tropicalia, tropicalismo